What Killed the Radio Star? The Frisian Claim to Radio Fame

- Hans Faber

- Apr 3, 2023

- 17 min read

Updated: Jan 20

The Second World War. Despite a clear warning from the German Wehrmacht to buzz off, the nosy and inquisitive Hanso Idzerda returned to the crash site of a V2 rocket on Parkweg Road in Scheveningen—not far from his own home. Ignoring the warning, he was caught a second time by a Wehrmacht patrol. This time, there would be no friendly asking anymore. On November 3, 1944, Idzerda was executed on charges of espionage at the estate of Oosterbeek. He had been investigating the crash site to collect debris from a V2 rocket whose launch from Haagse Bos Park had failed. It has been suggested he carried some fragments of the rocket in his pocket. It was not until September 1945 that Idzerda’s remains were discovered, revealing that he had been shot. The reasons for his perilous actions remain a matter of speculation: was it the reckless curiosity of an ignorant engineer, or, more heroically, a mission for the Resistance?

So, let’s assume it was simply curiosity that killed the cat. Why then should we dwell at length on this individual? Apparently a not overly bright and gaga personality, and one with little danger awareness. Well, we should. Hanso Idzerda, nicknamed the Dutch Marconi, is one of the world’s godfathers of radio broadcasting as we know it today. Popular Bomenbuurt 'trees borough' in the city of The Hague at the North Sea coast is where all this wireless modernity happened more than a century ago. His factory, now turned into apartments, is still there to see, although it needs a paint job. Its address details will be disclosed in this blog post. Idzerda’s story, however, started in the less exciting, small village of Weidum in the province of Friesland.

radio pioneer

Hanso Idzerda was born in 1885 in sleepy Weidum, a terp village south of the town of Leeuwarden. His full name—please, take a deep breath—was Hans Henricus Schotanus à Steringa Idzerda. Later in life, when working on radio and broadcasting innovations, Idzerda was also known as I.D.Z. or Idz. His father was a doctor, but that did not prevent young Hanso from choosing his own, very different path. At first, Idzerda studied at the Machinistenschool ‘school for marine engineers’ in the city of Amsterdam. Apparently, this school did not meet his expectations, and he decided to study electrical engineering at the Rheinisches Technikum in the town of Bingen am Rhein in Germany. He finished his study Elektrochnik in 1908 (Vallinga 2019). Bingen, by the way, is not too far remote from the Lorelei Rock where many early-medieval Frisian skipper narrowly escaped death; check our blog post Late Little Prayers at the Lorelei Rock. Reckless Rhine Skippers in Distress for more.

After his study in Bingen, engineer Idzerda starts working for the German company Siemens-Schuckert in Amsterdam. Not long after, in 1913, Idzerda moves to Scheveningen, a coastal fishing village close to the city of The Hague. Establishing himself at Scheveningen was no coincidence. Here, both the radio station of the Ministry of War, transmitting morse across the seven seas, and the state-owned Rijkstelegraaf 'national telegraph' (later PTT) were located, and to which he hoped to sell his instruments (Höller 2019, De Raadt 2023). A year later, in Scheveningen-The Hague, Idzerda started to work as independent wireless advisor, with Technisch Bureau Wireless 'technical bureau wireless' as the name of his first enterprise. In 1918, Technisch Bureau Wireless was renamed Nederlandsche Radio-Industrie ‘Netherlands radio industry’ (NRI). Again a privately owned company of Idzerda. NRI company manufactured parts for radio sets. His factory was located on 8-10 Beukstraat St in The Hague.

Already during the First World War (1914-1918), Idzerda experimented in the rectory of his father-in-law in the village of Mantgum in the province of Friesland. He developed valves or tubes that allowed him to receive Morse communication and follow the movements of zeppelins. Stories are that Idzerda was fortunate because after one of the zeppelins crashed, he somehow managed to get his hands on one of the valves, which he would improve together with the Philips firm (Höller 2019). Others say Idzerda obtained the valves through fencing from a Telefunken radio of a crashed German fighter plane. An airplane crashed either on the Wadden Sea island of Texel or into the Zuiderzee 'southern sea' in August or September 1917 (De Raadt 2023).

Truth is, Idzerda was actively approached by Capt. Kniphorst of the Radiotelegraafdienst 'wireless telegraph service' of the Dutch army to build receivers to locate illegal wireless telegraph transmitters (Bangma et al 2022). Probably, the Radiotelegraafdienst and Idzerda were familiar with each other since Idzerda had established himself in Scheveningen in 1913 to be close to the Ministry of War. Idzerda succeeded in his assignment, and listening stations were set up in several towns in the Netherlands. An unforeseen bycatch was that the army could now also track the movements of German zeppelins passing through Dutch airspace at night on their way to England and back. The Netherlands was neutral during the First World War, and these zeppelins violated that status. The Germans were baffled by how the Dutch discovered the movements of the zeppelins.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, radio technology was used almost exclusively for maritime and military purposes, mainly for transmitting Morse code—an innovation introduced by the Italian Nobel Prize laureate Guglielmo Marconi in 1895. Until the First World War, wireless voice transmission was still impossible. Because radio was considered strategically important for national security, free use of the airwaves was prohibited. Anyone wishing to transmit airwaves required explicit government permission. Privately owned receivers capable of picking up Morse signals were initially banned as well. By 1917, however, the Dutch government had grown intelligent enough to acknowledge that such a ban was unenforceable among nearly 7 million citizens. Receivers were therefore permitted from that year onward.

In 1916, Philips Gloeilampenfabriek ‘Philips light bulbs factory’ and Idzerda jointly started experimenting to produce triode valves called gloeilampdetectoren in the Dutch language. Valves after the example developed in 1907 by the American inventor Lee de Forest (1873-1961). Two years later, Idzerda and Philips concluded a contract whereby Philips promised to produce Idzerda’s new triode valves, and Idzerda committed himself to purchase a minimum of 180 valves per year. The new valves were marketed under the name 'Philips IDEEZET lamp', for sale at 12.50 guilders a piece. Idzerda sold the triode valves via his enterprise Technisch Bureau Wireless. Other names for these generator lamps were 'IDEEZET tube' and 'Dutch IDZ valve'. It turned out to be a great success for both Idzerda and Philips. During the first year, 1,200 items were sold, and in total several thousands (De Boer 1969, Bathgate 2020)—that's money, in all its meanings.

The word IDEEZET, by the way, is composed of the first three letters of the name Idzerda as pronounced phonetically in Dutch—I.D.Z., or Idz—which was, as noted, Idzerda’s common nickname. This forms an interesting parallel with another inventor, John Logie Baird (1888–1946), who developed television and whose name was likewise abbreviated to JLB (BBC 2025). Moreover, Idz was a Frisian from the north who moved southwards to Scheveningen, by the sea, JLB was a Scot from the north who settled in Hastings, also by the sea, on the opposite side of the Channel—both, in their own way, bridging the North Sea with waves.

After the introduction of the Philips IDEEZET lamp, radio amateurs switched from crystal receivers to these new tube receivers, which were far more sensitive than the crystal ones. Dutch journalist and radio-amateur Jan Corver produced a do-it-yourself manual to build your own top-notch receiver. These one-lamp receivers were capable of receiving signals from a much greater distance than so far. Corver is also the one who later coined the Dutch terms omroep 'broadcaster' and omroeper 'announcer'.

evening musical

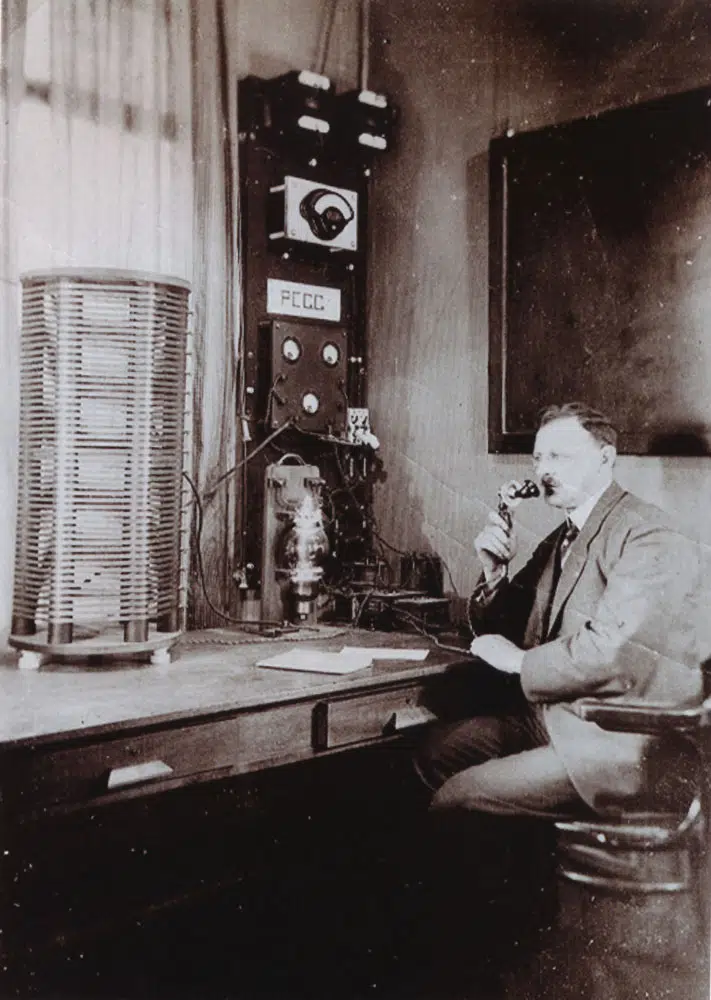

Primarily to boost sales of the radio receivers produced by his NRI company, Idzerda sought to begin regular broadcasting (Marks 2012). On August 19, 1919, he obtained a licence from the Ministerie van Waterstaat 'ministry of water management' under the randomly assigned call sign PCGG, an abbreviation without any particular meaning. PCGG’s inaugural broadcast took place on Thursday, 6 November 1919, sponsored by the Philips company.

Earlier that year, between 24 February and 8 March, Idzerda had demonstrated at the yearly Jaarbeurs trade fair on Vreeburg Square in Utrecht that he could transmit sound over a distance of 1,200 metres. The transmitted audio came from a small musical box. Not only 1,200 meters were covered; a listener twelve kilometers outside Utrecht also received the musical box—loud and clear!

The historic first radio broadcast on November 6 was named Radio Soirée-Musicale (sic), which is French for ‘musical evening party,’ and transmitted on a longwave wavelength between 08:00 and 11:00 PM. Idzerda, by now 34 years of age, had announced his program beforehand on November 5 in the newspaper Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, NRC.

Program offered utilizing a phonograph by means of a Philips-Iduret-Generator lamp, fitted in a Radio-Telephone Broadcast Station of the Netherlands Radio-Industry at a wavelength of 670 Meter. Everyone possessing a simple Radio-receiving device can listen to this music relaxed at home. By making use of our amplifiers it is possible to hear the music in the entire room. For more information and delivery of receiving devices, amplifiers, telephone broadcasting stations etc please contact the Netherlands Radio Industry at Beukstraat 8-10, The Hague.

During the programs, 'presenter' Hanso Idzerda not only introduced the records he played but also answered technical questions from listeners who telephoned. In addition, Idzerda told funny little stories he had tried on his children before. Records played that first evening were Turf in je ransel ‘peat in your rucksack/haversack’, a grenadier march, and Een meisje dat men nooit vergeet ‘a girl people never forget’. His announcements were in three languages: Dutch, French, and English, revealing his international aspirations. Thursdays between 20:00 and 23:00 hours continued to be his fixed broadcasting time, even though there were periods when he additionally broadcasted on Sundays, too. From November 1921, Idzerda obtained a new license, which allowed him to broadcast four times a week in the afternoons, on Mondays, Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays.

Idzerda’s tremendous success can be attributed to several factors. From 1918 onward, he was already producing radio tubes, and by the time he began broadcasting in 1919, an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 radio receivers were effectively 'waiting' for something to tune in to. In addition, he had built a remarkably powerful transmitter with exceptional range. Thanks to this long-reach transmitter, his programmes were soon audible across the North Sea, and listeners in southeast England quickly became devoted followers of Dutch radio. Remarkably, this happened before the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) was founded in October 1922. Some even argue that Idzerda’s broadcasts helped inspire the creation of the BBC (De Raadt 2023). Before long, his transmissions were being picked up in Belgium, France, Germany, and possibly even as far away as Iceland.

Idzerda is probably also the first in the world to make a recording studio, which he called klankzaal ‘sound room’ or paleis van stilte ‘palace of silence’. It was draped with curtains to achieve the best sound quality (De Raadt 2023). Nice anecdote is that when Idzerda was on air he had on the door of the klankzaal a light bulb on, with a sign saying:

"Brandt dit licht dan koppen dicht!"

burns this light then shut up!

In the UK, Idzerda’s PCGG became commonly known as the Dutch Concerts station. PCGG also got the attention of the newspaper London Daily Mail. Together with the Marconi company, the Daily Mail was busy giving publicity broadcasts. However, the Office of the Postmaster General gave no permission. If they cannot go left, they go right. So, the Daily Mail turned to Idzerda's PCGG to make publicity from overseas. Of course, in return for money. For one year, Idzerda made programs especially for the Daily Mail. At first, these were broadcast on Thursdays and Sundays. Later, only on Sundays. But then a program of two hours, instead of the previously scheduled one hour twice a week.

On July 27, 1922, the first time Idzerda broadcasted for the Daily Mail, he featured on his show singer Lily Payling of which Idzerda later said: “She had so many pretensions regarding accompaniment, accommodation, care, locality, and what a spoiled artist can invent more, that I had to rest for a week after the broadcast to recover from it.” Nevertheless, her radio performance was the first of its kind ever. It generated a lot of interest in the UK, with big loudspeakers placed on streets so the public could hear Lily sing all the way from Scheveningen (Lyncombe 2018).

The concert performed by the Residentie Orkest, led by conductor Peter van Anrooy, on the occasion of the twenty-five anniversary of Queen Wilhelmina’s reign on September 1, 1923, was also broadcasted by Idzerda (Höller 2019). Of course, this was quite an honour that fell upon Idzerda.

"We’ve got a thing that’s called radar love. We’ve got a wave in the air. Radar love."

Golden Earring, 1973

Between July and September 1924, with financial support from the Maatschappij Zeebad Scheveningen 'society sea-bath Scheveningen', Idzerda broadcast a special series known as 'Kurhaus Concerts'. Broadcast from the luxurious Koninklijke Loge of the Kurhaus 'spa house' at the beach of Scheveningen. However, financially this initiative turned out to be too demanding for Idzerda. The quality of the broadcasting was too poor, and the audience became increasingly limited.

By the way, more technical innovations entertaining the public had been presented in the Kurhaus. In 1896, the Kurhaus was where for the first time in the Netherlands motion pictures were played with a cinematograph daily. So, it was also the first cinema.

Besides financial difficulties due to the expensive Kurhaus Concerts, the Philips company and Idzerda ended their cooperation in September 1924 as well. The love was over, if there ever was any. Some say it was because Idzerda was a difficult personality. Possibly, Philips saw more lucrative commercial activities elsewhere. A year before, namely, the Nationale Seintoestellen Fabriek ‘national transmitters factory’ (NSF) had begun broadcasting from the town of Hilversum in central Netherlands, and NSF worked together with Philips (Vallinga 2019). From the spring of 1923 onward, Radio Hilversum started broadcasting from the center of the country, which meant strong competition for PCGG. Whatever the exact reasons, Idzerda soon ran out of financial means to continue his operations. Eventually, he went bankrupt and lost his broadcasting license in 1924.

Two years after the bankruptcy, on June 17, 1926, Idzerda obtained a new broadcasting license for his new company named Idzerda Radio, also located on 8-10 Beukstraat St in The Hague. This time it was issued by the government for the purpose of technical experiments only. However, after midnight, when the programs of NSF in Hilversum had ended, Idzerda had his own illegal program called De Felicitatiedienst, ‘the congratulation service.’ Strictly speaking, Idzerda had turned into a radio pirate. Bad Hanso, bad bad Idz! After 1930, his license would not be renewed anymore. That was when the curtains fell for Idzerda as a radio star, and in 1935 he ended all radio activity definitively. The end of the radar love. Together with his other love, his wife Wilhelmina, he started a pension in Scheveningen.

The real reason, we think, for Idzerda's downfall was not the expensive ventures and his supposedly difficult, perfectionist, or non-commercial character, or any combination thereof, as is often said. No, Idzerda did not keep pace with the fast-evolving innovations in communication technology. This means his initially great quality of wireless sound was not really improving and fell behind the competition, resulting in less interest, fewer investors, and less revenue. As often happens, continuous innovation and progress are key, especially when your company is operating in a fast-growing, experimental market.

who’s got the biggest?

What about the Frisian Claim for Radio Fame? The claim for being the first broadcaster of the world?

For the names of five other generally accepted co-competitors for this claim for fame, we must go West, and cross the water waves of the Atlantic.

1906—A first competitor is the Canadian Reginald Fessenden. In November 1906, Fessenden's experiments succeeded in transmitting speech. A month later, on Christmas Eve, he made a broadcast from his workshop in Chestnut Hill in the state of Massachusetts. Fessenden played some records, including Händel’s Largo, and he played a solo of Gounod’s Oh Holy Night on the violin. Furthermore, of course, he read from the Gospel of Luke. It was, after all, Christmas Eve. Fessenden announced his program beforehand with Morse messages to radio operators of sea vessels. On New Year's Eve, he repeated the broadcast. It was the first public broadcast of voice, albeit only a two-time event.

1912—A very strong competitor was the American Charles David Herrold, who broadcast voice on a regular basis on Wednesdays between 1912 and 1917. His students called him Doc, though he never held a degree, and he should not be confused with that other Doc, the inventor Emmet Brown. Though Doc's broadcasts were public, they were weak and could only be heard in the city of San Jose itself. In 1917, the government suspended all broadcasting because America had entered the First World War. Four years later, in 1921, he started broadcasting again under the call sign KQW, until 1926, when he quit and left the wireless world behind.

Herrold, the self-proclaimed Father of Broadcasting (Bathgate 2020), was based in the city of San Jose in the state of California. “San Jose Calling!” as he usually started the program. Herrold founded the Herrold College of Wireless and Engineering, and thought radio was good publicity for his college. His broadcasts were aimed at students and consisted of giving the news, playing records, and making advertisement. Herrold’s broadcasts were pre-announced in the local newspaper, and his first planned broadcast was in 1912 (Bathgate 2020, Ewbank 2020). Note that the term 'broadcasting' was coined by Harrold, too. Harrold was son of a farmer, and 'broad casting' in this profession meant spreading seed over a large expanse (Bathgate 2020).

1914—A third competitor is the Flemish Robert Goldschmidt. He started broadcasting on March 23, 1914, from the Palace in Laeken (Brussels), Belgium. Unfortunately, a few months later, Belgium was dragged into the First World War, and the German army destroyed his brand-new station.

1916—A fourth competitor is inventor Lee de Forest. We already mentioned him for developing the triode valve, which he patented in 1907. In November 1916, he transmitted the first presidential election from his station in the Bronx in the state of New York. Later, he moved his station to High Bridge in New York. De Forest, too, had to suspend all activity when America entered the First World War in 1917. After the war, he moved to the state of California and started broadcasting there in November 1921. However, we are not aware that de Forest's broadcasts had regular, planned programming.

1920—A fifth competitor is the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company in Pittsburgh, in the state of Pennsylvania, of Leo Rosenberg. Under the call sign KDKA, it started broadcasting on November 2, 1920. KDKA had a license to broadcast. November 2, 1920, is widely regarded around the globe as the start of commercial broadcasting. Alas, at least Idzerda’s PCGG beat Rosenberg's KDKA by a full year already.

Lastly, we arrive at competitor number six, Hanso Idzerda, who started broadcasting in 1919.

Frankly, the answer to who is the godfather of radio broadcasting out of these six competitors depends on the definition of 'godfather' you formulate. Preferably beforehand, so you know the outcome and who wins the competition.

In general, however, there seems to be agreement that it should be more than a one-hit wonder. And that the programming must be announced ahead of its broadcasting. Additionally, you can enrich your definition with elements like ‘internationally’ and ‘commercially’. Adding 'internationally' to your definition is lucrative when your favourite radio hero lived in a small country where abroad is never far away. The Netherlands is such a small country where the world is never far away, in contrast to, for example, the United States. This is underlined when the presenter announces the program in three different languages, as we have seen in this blog post. Lastly, opinions differ on whether or not a license to broadcast should be a prerequisite. Some argue a license is not relevant to be eligible for the award of being the first broadcast company in the world. This is fine, but then we are, in fact, talking about pirates (see note 3 further below).

When we formulate the question 'who founded the first licensed, commercial broadcasting company in the world, catering pre-announced public programs on a regular basis to a large international audience?' it must be Hanso Idzerda. Yes, by far. This accomplishment in itself makes Idzerda one of the greatest radio pioneers already. But besides his broadcasting activities, Idzerda also invented much more sensitive valves, and he developed transmitters and receivers of the highest standard hitherto. Everything together, we think, makes Hanso Idzerda truly stand out from the radio crowd, regardless of whatever biased, nationalistic definition you use. A pity, though, the tragedy and pointlessness of war did not spare him.

— V2 Killed the Radio Star —

Curious cat Hanso Idzerda is (re-)buried at the beautiful and old graveyard 'Nieuw Eyk en Duynen' in The Hague, just south of neighbourhood Bomenbuurt, where his firm NRI once stood.

Note 1 — Another famous Frisian, and contemporary of Hanso Idzerda, who was also executed for alleged espionage, is Margaretha Geertruida (Grietje) Zelle (1876-1917) from the town of Leeuwarden, better known by her artist's name Mata Hari. She also lived for a while in The Hague, during the years 1915 and 1916, at Nieuwe Uitleg St. 16.

Note 2 — Idzerda was, as explained in this blog post, one of worlds first radio presenters. The well known American broadcaster and CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite (1906-2009) was of Frisian decent as well. His ancestor who migrated to New Amsterdam (later New York City) was Theunis Hercksen Krankheyt (1655–1709), Theunis decents from Herck Syboutszen Kranckheyt (born 1620), a farmer and ship carpenter from the district of Zevenwouden in the province of Friesland. Herck migrated to Newtown, Queens, in 1940. The surname Kranckheyt (Cronkite) means 'illness', by the way. Nevertheless, Walter reached a very respectable age.

Note 3 — The Hague-Scheveningen, where Hanso Idzerda lived and broadcasted his radio shows, is also where in 1973 a radio pirate ship ran aground during a heavy storm. It was the ship of the radio pirate Veronica. The ship was called the Norderney, after the Frisian Wadden Sea island in the region of Ostfriesland, Germany. Originally, the Norderney was an Icelandic fish trawler. Radio Veronica, started broadcasting outside Dutch territorial waters at sea in 1960. Of course, this broadcaster had no permit, and hence a radio pirate. Comparable to the construct of the Daily Mail and Hanso Idzerda before. Initially Veronica was named Vrije Radio Omroep Nederland ‘free radio broadcasting Netherlands’ (VRON), but this name was confused with the Vereniging Experimenteel Radio Onderzoek ‘foundation experimental radio research’ (VERON). Hence the name Veronica.

Anyway, The Hague-Scheveningen seems to be an experimental radio hotspot.

One last thing, ship the Norderney was the second ship of Radio Veronica. The first ship was called the Borkum Riff, again named after a Frisian Wadden Sea island, namely Borkum in the region of Ostfriesland. Originally, the Borkum Riff was a German light vessel.

Another famous radio pirate was Radio North Sea International (RNI) that started broadcasting from sea in 1970. It was owned by Swiss businessmen. The ship was named the Silvretta and built in the village of Slikkerveer in the Netherlands, and renamed Mebo II. Later, RNI temporarily renamed itself Radio Caroline International, and started to make propaganda in favour of the Tory party in the UK.

Later that year, RNI came into conflict with Radio Veronica. It was businessman Kees Manders who tried to enter the Mebo II with the ships Husky and The Viking. At the end, the Netherlands Royal Navy had to intervene in the conflict. A year later, on May 15th, three men paid by Radio Veronica left with a rubber boat from Scheveningen, and placed explosives on the Mebo II. The bomb was detonated and the Mebo II send out an SOS distress. Director Hendrik Verweij and advertisement manager Norbert Jurgens of Radio Veronica were the brains behind the bombing. They were arrested and convicted (Bathgate 2020). It was the end of a violent episode in radio history.

Note 4 — As explained in this blog post, George Frideric Händel’s Largo was one of the first musical composition to enjoy over the radio ever, which was in 1906. Radio pioneer Reginald Fessenden had good taste, since the most famous Frisian pelota player ever, Hotze Schuil from port town Harlingen, had precisely this composition played at his funeral in 2005. See our blog post Donkey King of the Paulme Game. From Kaatsen to Tennis and Jai-alai for more about this legendary sportsman and the game of kaatsen.

Suggested music

Golden Earring, Radar Love (1973)

The Buggles, Video Killed the Radio Star (1980)

Queen, Radio Ga Ga (1984)

R.E.M., Radio Song (1991)

Further reading

Adams, M., The First Radio Station (2009)

Bangma, K., Dijkstra, N., Graaf, de S. & Mud, R., Friesland en de Friezen in de Eerste Wereldoorlog (2022)

Bathgate, G., Radio broadcasting. A History of the Airwaves (2020)

BBC, JLB: The Man Who Saw the Future (2025)

Boer, de P.A., à Steringa Idzerda. De pionier van de radio-omroep (1969)

Ewbank, A., Site of the World’s First Radio Broadcasting Station (2020)

Federal Communications Commission, Celebrating 100 Years of Commercial Radio (2020)

Historiek, Eerste Radio-uitzending in Nederland (website)

Höller, R., "Brandt dit licht dan koppen dicht!" (2019)

Kerensa, P. (podcast), British Broadcasting Century. 100 years of the BBC, radio & life as we know it. Hanso Idzerda and the Dutch Concerts — with Gordon Bathgate (2022)

Koolhaas, M., Was Idzerda de eerste ter wereld? 90 jaar radio-omroep in Nederland (2009)

Laan, van der T., Zolderpionier Hanso Idzerda uit Weidum maakte als eerste Nederlander ooit radio (2019)

Lyncombe, Payling, Lily (2018)

Marks, J., British Radio at 90. But where’s Idzerda? (2012)

Mathis, W. & Titze, A., 100 Years of Wireless Telephony in Germany: Experimental Radio Transmission from Eberswalde and Königs Wusterhausen (2021)

Meerschaut, van den P., Brandt dit licht... dan koppen dicht. De pioniersjaren van de radio tot 1925 (2019)

Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld & Geluid, The Birth of Radio Broadcasting (2016)

Popular Wireless weekly, The Dutchman (1923)

Raadt, de K., ir. Hanso Henricus Schotanus â Steringa – Idzerda (1885-1944) (2023)

Rowe, L., 10 Oldest Radio Stations Of All Time (2022)

Schelven, van A.L., Idzerda, Hans Henricus Schotanus Steringa (1885-1944) (1979)

Son, H., Making (FM) Waves: How Radio Changed the World (2019)

Stichting Haags Industrieel Erfgoed (SCHIE), Nederlandsche Radio-Industrie (NRI), 1913-1924 (webite)

Strengholt, J.M., Gospel in the Air. 50 years of Christian witness through radio in the Arab World (2008)

Vallinga, M., Hanso Idzerda: het tragische leven van een radiopionier (2019)

Vereniging voor Experimenteel Radio Onderzoek in Nederland (VERON), Idzerda Day 100 jaar radio (2019)

Comments