Shipwrecked People of the Salt Marshes

- Hans Faber

- Dec 1, 2019

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 1, 2025

Tidal marshlands and Frisians, a dual entity. The Chauci and the Frisians—referred to by the Romans as Frisii or Fresones—had learned to adapt to an unprotected yet strangely hospitable salty world: a vast, treeless expanse of tidal marshlands. No rocks, no forests, scarce fresh water, and regularly flooded by a cold, relentless sea. Quoad arbores est quasi nuda—'as for trees, it is almost bare'—is how the marshes of Frisia were once described (De Graaf 2004). Yet despite this harsh landscape, when the so-called sophisticated and civilized Romans arrived at this watery edge of the world at the dawn of the Common Era, they found the Chauci and Frisians to be thriving, prosperous tribes. Their secret? They lived on terps—artificial dwelling mounds—and in the region of Nordfriesland in Germany, they still do to this very day.

It was the Roman soldier and scholar Plinius—better known as Pliny the Elder (ca. AD 23–79)—who described the terp culture in his Naturalis Historia, written in the first century. Pliny had been stationed for several years in the area between the rivers Ems and Weser, the homeland of the Chauci. At that time, the terp region stretched across what is now roughly the area of Ostfriesland in northwest Germany, together with the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen in the north of the Netherlands. Terps existed even further east along the banks of the Lower River Weser, of which archaeological research of the terps of Fallward and Feddersen is proof.

Generally, the tribe of the Chauci is situated in the region of Ostfriesland and possibly in the eastern parts of the province of Groningen as well. The Frisians were the neighbouring tribe living to the west of the Chauci, roughly corresponding to the modern provinces of Friesland and Noord Holland north of the (former) River IJ, an area that the Romans failed to conquer long-term. After a few decades of trying to gain control over the territories of the Chauci and Frisians, the Romans settled for the Lower River Rhine as the northernmost border of their gigantic empire on the Continent, called the Lower Germanic Limes, or simply limes.

Below is what Plinius wrote about the Chauci, regarding the terp culture bordering the coast of the Wadden Sea.

“We have discussed that at least in the east there are several peoples along the coast of the ocean who have to live without trees and shrubs. And we have also seen such peoples in the north, namely the Chauci, both the Great Chauci and the Smaller Chauci. Twice a day over an immeasurable distance the ocean comes up with enormous amounts of water, and covers an area eternally disputed by nature, and of which it is unclear whether it belongs to the mainland or is part of the sea.

There, this poor people occupy high dwelling mounds or dams that they single-handedly have raised to the highest water level they experienced. With their huts they have built on it, they look like sailors when water covers the surrounding land. But they look like shipwrecked when the water has withdrawn, and they hunt around their huts for fish that flee with the sea.

They cannot keep cattle and feed on milk like neighbouring peoples. And, because no scrub grows in the wider area, it is impossible for them to fight with [hunt for] wild animals. From reed and bulrush, they weave rope to tie fishing nets. They collect mire by hand that they let it dry through the wind, more than through the sun. With this peat they heat their food and their bodies churned by the northern wind. They only drink rainwater, which they keep in pits at the entrances of their house.

And these peoples speak of slavery when they are conquered by the Roman people today! That is indeed how it goes: fate leaves many people alive to punish them.”

transl. by Looijenga, Popkema & Slofstra

One cannot say Plinius was particularly in love with the place, but luckily there are people who also commemorate things they experience in life that they did not enjoy. It leaves us with a unique description of how life was two thousand years ago in the Wadden Sea area. For one thing, the treelessness, the mound earthworks, i.e., terps, the fresh water supply, and the fishing weirs and traps are of interest and are recognizable from archaeological research.

Concerning the pits filled with rainwater, probably collected from the house roofs, they might refer to what is known in the region of Nordfriesland as a feeting or feith, in the province of Friesland as a dobbe, and in the province of Groningen as a dob. Check our post Groove is in the Hearth. Very superstitious, is the way about collecting rainwater with grooves on terps, and all the superstitious and pagan practices that were once part of it. Dobbe or feeting earthworks are now mainly used on the tidal marshlands for the freshwater supply for livestock; cattle, sheep, and horses. You can find many at the tidal marshlands of Noarderleech in the province of Friesland.

Errata in Plinius’ travel journal

There are, however, some errors or misunderstandings in the account of Plinius.

The mire Plinius mentioned must have been either cow dung or manure because clay does not burn. At most, it turns into stone. Cow dung, on the other hand, can be dried and then used as fuel. This dung-drying practice continued to be observed in the terp region of Nordfriesland in northern Germany even after the Second World War, where terps, locally known as Warften, maintain their protective function to this very day, albeit things are becoming critical with the sea level rise due to climate change. The other option might be that Plinius actually meant peat instead of mire. However, for the peatlands, you are already a bit more inland, away from the terps and the salt marshes—not an area regularly flooded. Our guess, therefore, is that it was cow dung.

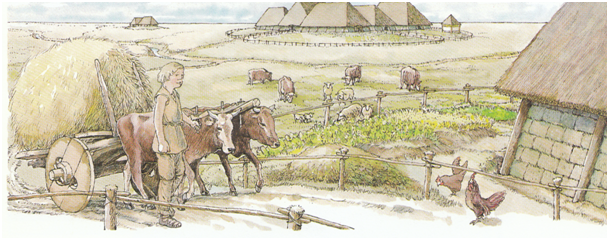

Furthermore, the report that the Chauci—and the Frisians—did not have cattle is incorrect. On the contrary, peoples dwelling on the tidal marshlands were livestock farmers par excellence, both cattle and sheep. Livestock husbandry was even one of the primary foundations of their economy (Nieuwhof 2018, Siegmüller 2022). Additionally, from the Romans, the terp dwellers inherited, among other things, chickens and cats, too. Archaeological research has proven cow and sheep husbandry without any doubt. In other Roman accounts, that of the historian Tacitus (ca. 56-117), cattle breeding is specifically mentioned.

There is no explanation as to why Plinius missed this 'little detail' or wanted to miss this detail. Some argue that Plinius described a situation shortly after a storm flood (Dirks 2023), but we humble hikers think that is not very likely. It does not change a thing concerning the presence of cattle. Whatever the reason for Plinius' poor observation, if only he had known that the Friesian cow breed would dominate dairy production worldwide in modern history. For the world history of dairy, go to our blog post Golden Calves, or Bursting Udders on Bony Legs?

There is another first-century account about the peoples living in the coastal zone of the North Sea, namely that of Nicolaus of Damascus, a Roman-Greek historian who lived in the late first century. He described that the Celts—note that the Romans initially made no distinction between Germans and Celts—who lived near the sea considered it a disgrace to flee when the walls of their houses crumbled. When floods penetrated the land, they confronted it armed until they were dragged into the sea. If they were to flee, people might accuse them of being afraid of death (Looienga, Popkema & Slofstra 2017).

With regard to the Celtic nationality, there are indications the Frisians (Frisii) of the Late Iron Age were indeed a Celtic people, or an admixture with the Germanics at least. For more, read our blog post Barbarians riding to the Capital to claim rights on farmland.

Note 1 — Although Plinius spoke of the Chauci and the Frisians as inferior peoples, they were the tribes that started raiding and pillaging from the second century onward the coasts of the Western Netherlands, the coast of the Southern Bight, the English Channel, Brittany, and way beyond. In the third century, piracy had reached such proportions that it gave the Romans more than a headache. Meanwhile, a new North Sea Germanic culture was being forged. Read more in our blog post Our civilization — it all began with piracy or A raider’s portrait from Appels. The water world of the Migration Period.

In addition, during the Migration Period coinciding with the demise of the Western Roman Empire, the terp dwellers of the Elbe-Weser triangle, the so-called Old Saxons, fanned out over much of the southern coastal zone of the North Sea. They repopulated the Frisian marshlands that had been nearly abandoned between 325 and 425 and, moreover, created the Anglo-Saxon culture in eastern England. The Anglo-Saxon culture, in turn, had a profound impact on the history of the world. If one considers the region of Holland as having evolved from partly Frisian origins, this region would also have a major impact on the history of the world during the Early Modern Period of the Dutch Republic. Anyway, both shores of the Southern Bight of the North Sea, viz. England and Holland, together have helped shape the world fundamentally. We refrain from giving it an appreciation of whether that was a positive or negative influence.

If interested who the 'Saxons' from the Elbe-Weser triangle were, read our blog post The Deer Hunter of Fallward, and his Throne of the Marsh.

Note 2 — The original journal of Plinius:

Diximus et in oriente quidem iuxta oceanum complures ea in necessitate gentes. sunt vero et in septentrione visae nobis Chaucorum, qui maiores minoresque appellantur. vasto ibi meatu bis dierum noctiumque singularum intervallis effusus in inmensum agitur oceanus, operiens aeternam rerum naturae controversiam dubiamque terrae [sit] an partem manibus ad experimenta altissima aestus, casis ita inpositis navigantibus similes, cum integant aquae circumdata, naufragis vero, cum recesserint, fugientes que cum mari pistes circa tuguria venantur. non pecudem his habere, non latte ali, ut finitissimis, ne cum feris quidem dimicare contingit omni procul abacto frutice. ulva et palustri iunco funes nectunt ad praetexenda piscibus retia captumque manibus lutum ventis magis quam sole siccantes terra cibos et rigentia septentrione viscera sua urunt. potus non nisi ex imbre servato scrobibus in vestibulo domus. et haec genres, si vincantur hodie a populo Romano, servire se dicunt! ita est profecto: multis fortuna parcit in poenam.

Suggested music

Les Misérables, Do You Hear the People Sing? (1980)

Blondie, The Tide Is High (1980)

Aerosmith, Living on the Edge (1993)

Further reading

Bank, J. & Bosscher, D., Omringd door water. De geschiedenis van de 25 Nederlandse eilanden (2021)

Dhaeze, W., The Roman North Sea and Channel Coastal Defence. Germanic Seaborne Raids and the Roman Repsonse (2019)

Dirks, C.H., Geschichte Ostfrieslands. Von der Freiheit der Friesen bis zu Deutschlands witzigstem Otto (2023)

Gelder, van J. et al, Plinius. De wereld. Naturalis historia (2004)

Graaf, de R., Oorlog om Holland 1000-1375 (2004)

Guðmundsdóttir, L., Wood procurement in Norse Greenland (11th to 15th c. AD) (2021)

Hagen, J., Een ‘armzalig’ volk bouwt terpen en dijken (2021)

Hines, J. & IJssennagger-van der Pluijm, N.L. (eds.), Frisians of the Early Middle Ages (2021)

Historiek, “Een meelijwekkend volk” — Plinius over Friezen (2023)

Lasance, A., Wizo van Vlaanderen. Itinerarium Fresiae of Een rondreis door de Lage Landen (2012)

Loveluck, C. & Tys, D., Coastal societies, exchange and identity along the Channel and southern North Sea shores of Europe, AD 600–1000 (2006)

Looijenga, A., Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B. (transl.), Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

Nedelius, S., Early Germanic Dialects — Old Frisian (2019)

Nieuwhof, A., Dagelijks leven op terpen en wierden (2018)

Nieuwhof, A., Ezinge Revisited. The Ancient Roots of a Terp Settlement (2020)

Nijdam, J.A., ‘De gemaskerde Wizo: vervalsing, mystificatie of pastiche?’. Bespreking van: Wizo van Vlaanderen, Itinerarium Fresiae (2012)

Popkema, A.T., Jammerdearlik folk oan natoer har swetten (2023)

Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Panorama Landschap — IJsseldelta (website)

Schepers, M., Cancelling Plinius? Reflecties op de rol van het misera gens-citaat in de geschiedschrijving van het terpengebied (2023)

Siegmüller, A., Dwelling mounds and their environment. The use of resources in the Roman Iron Age (2022)

Teetied & Rosinenbrot (podcast), Warften? Komm wir schütten einen Hügel auf! (2023)

Featured images by Jouke Nijman, Samson J. Goetze, and Ulco Glimmerveen.

Comments